DNA Sequencing

The evolution and future of DNA sequencing

The evolution of DNA sequencing – from Sanger to cutting-edge next generation approaches like Illumina, Nanopore and Single Molecule, Real-Time (PacBio) sequencing – has brought advances in speed, cost and accessibility. However, what challenges are faced in throughput scale-up, and what promise does automation hold for transforming genomics and personalised medicine?

Andrea Patrignani at INTEGRA Biosciences

DNA sequencing is a cornerstone of modern life sciences, providing the detailed genetic information that is critical to making advancements in medicine, agriculture, biotechnology and beyond. It plays a central role in identifying mutations that cause specific disease phenotypes and unravelling their mechanisms, as well as supporting the development of effective, personalised treatments with fewer side effects. In addition, sequencing the genomes of pathogens – such as viruses and bacteria – enhances our understanding of their evolution, spread and drug resistance, driving innovations including messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines.

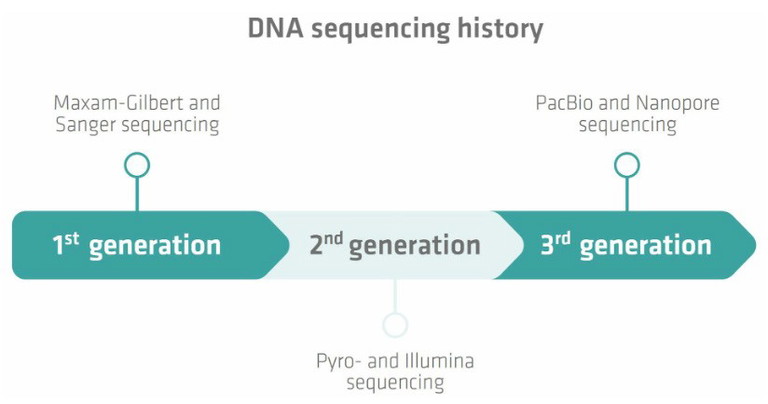

Despite its importance for multiple areas of science, DNA sequencing actually has a relatively short history. The first major breakthrough was achieved in 1977 when two methods – Maxam-Gilbert and Sanger sequencing – were developed (Figure 1).1,2 Sanger sequencing was the more accurate, robust and easy to use of the two options, and so became the favoured approach. This technique has come a long way over the last few decades, and significant improvements were made to Sanger sequencing to meet the demands of the Human Genome Project.3

The leap from single reads to high throughput

Sanger sequencing marked a significant advancement for genomics, but was constrained by its ability to only process one DNA fragment at a time. The growing demand for faster and more cost-effective techniques underscored the need for new methods capable of sequencing multiple fragments simultaneously. This issue was addressed in the late 1990s with the advent of pyrosequencing, developed by researchers at the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, Sweden.4 Pyrosequencing detects the release of pyrophosphate during DNA synthesis and served as a foundation for the development of next-generation sequencing (NGS), a high throughput approach capable of processing millions of DNA or RNA fragments in parallel.5,6 Over time, pyrosequencing-based methods were surpassed by more advanced NGS technologies, such as Illumina sequencing, which uses reversible terminator-bound deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs) during DNA synthesis.7 These second generation techniques revolutionised genomics once again, delivering unprecedented speed, scalability and throughput compared to the older Sanger method.

Figure 1: DNA sequencing has a short history, but is already in its third generation with PacBio SMRT and nanopore methods

The rapid progression of sequencing capabilities

The launch of Illumina’s first sequencing machine in 2007 marked a turning point for NGS, quickly establishing it as the dominant technology in the field.8,9 Despite its success, Illumina sequencing has limitations, particularly due to its reliance on DNA amplification. This step can obscure critical information, such as sequence abundance and nucleotide modifications, while also introducing copying errors and adding time and complexity to the workflow.10,11 To address these issues, single-molecule, long-read sequencing methods emerged, with Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) introducing its Single Molecule, Real-Time (SMRT) technology in 2011, followed by Oxford Nanopore Technologies launching nanopore sequencing in 2015.9 SMRT sequencing captures a fluorescent signal from each nucleotide incorporation to a newly replicated strand by a polymerase enzyme, while nanopore sequencing deciphers sequences by detecting base-specific electrical signals as single-stranded DNA passes through nanopores embedded in lipid membranes.9,12 Both technologies excel at resolving repetitive sequences, a challenging task for Sanger and Illumina methods.13,14

A notable advantage of NGS over Sanger sequencing is its heightened sensitivity. Sanger sequencing generates a single chromatogram per sample – representing the dominant DNA sequence present – which often masks minor variants if they are present in less than 15-20% of the DNA molecules.6,15 In contrast, NGS produces millions of parallel reads, which are computationally aligned and assembled, offering a detailed view of the sample’s genetic make-up. This means they have a much lower detection limit, and therefore a much higher sensitivity, because they analyse the nucleotide sequence of each molecule or fragment individually.15 For example, Illumina sequencing has a detection limit of just 1%, meaning it can detect rare variants present at very low frequencies within a mixed population of DNA molecules, providing exceptional resolution.6

Although largely replaced by NGS, Sanger sequencing remains in use globally due to certain advantages over newer methods. For instance, it is frequently employed to confirm gene variants identified through Illumina sequencing, owing to its remarkable accuracy of 99.99%.16 Consequently, Sanger sequencing retains a niche role in modern laboratories, at least for now.

“ Advances in NGS technologies have dramatically reduced sequencing costs over the past two decades, bringing the price of sequencing a human genome down to just a few hundred dollars ”

Automating NGS library preparation for enhanced productivity

Advances in NGS technologies have dramatically reduced sequencing costs over the past two decades, bringing the price of sequencing a human genome down to just a few hundred dollars.17 This affordability has made personalised medicine and genetic testing more accessible, illustrated by initiatives like the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH’s) All of Us research programme, which aims to sequence the genomes of over a million US citizens to build a diverse DNA database.18 Selecting the most suitable and cost-effective NGS method for a given application requires understanding the strengths and limitations of each approach and aligning these with specific research needs. Regardless of the method, achieving efficiency and accuracy in library preparation is critical for reliable results.

Advances in liquid handling now offer solutions to streamline this crucial step, improving productivity and scalability for genomics laboratories. Small benchtop robots can be used to integrate liquid handling steps of key processes like nucleic acid purification, adapter ligation, size selection, normalisation and pooling, while digital microfluidics platforms automate whole library preparation protocols in one run, including thermal cycling and magnetic bead-based operations. These automation solutions reduce hands-on time and standardise protocols, ensuring consistent and reproducible results across runs and locations.

A promising outlook for the field of genomics

In conclusion, NGS is a versatile and foundational tool that continues to dominate modern genomics, and its applications are now expanding across numerous industries, cementing its role in uncovering the complexities of the genetic world. Automating the critical library preparation step of NGS workflows further increases the potential and applications of this technique, paving the way for more reliable sequencing outcomes that contribute to scientific discoveries and personalised medicine approaches.

References:

1. Maxam A M et al (1977), ‘A new method for sequencing DNA’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 74(2), 560-564

2. Sanger F et al (1977), ‘DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 74(12), 5463-5467

5. Mashayekhi F et al (2007), ‘Analysis of read length limiting factors in Pyrosequencing chemistry’, Anal Biochem, 363(2), 275-287

9. Shendure J et al (2017), ‘DNA sequencing at 40: past, present and future’, Nature, 550(7676), 345-353

10. Petersen L M et al (2019), ‘Third-Generation Sequencing in the Clinical Laboratory: Exploring the Advantages and Challenges of Nanopore Sequencing’, J Clin Microbiol, 58(1), 1315-1319

11. Deamer D et al (2016), ‘Three decades of nanopore sequencing’, Nat Biotechnol, 34(5), 518-524

12. Visit: youtube.com/watch?v=mI0Fo9kaWqo

6. Visit: advancedseq.com/about-sanger-sequencing

18. Visit: allofus.nih.gov/

Andrea Patrignani, NGS sales specialist Europe at INTEGRA Biosciences, has over 20 years of experience in the genomics field, with expertise in managing and operating the latest NGS sequencing technologies. He joined INTEGRA in 2023 as an application specialist, providing training and support to European customers using technology for automated library preparation. In 2024, he took on his current role and is in direct contact with customers on a daily basis, sharing his vast experience and explaining how best to streamline NGS workflows.